On the poetics of Palermo & Sicily's cthonic grip

An ode to a city that influences my writing life

I am suffused within the honeyed light of the Mediterranean; I’m woozy with it. I’m on a Palermo balcony at dusk overlooking a silent, empty back alley that, by night, becomes a living, breathing womb of bodies. As if out of nowhere, there will soon be folding chairs and tables. And then the music. And then the voices will bounce between moss-covered buildings, which loom over the alleys and cobbled streets like crooked, darkened teeth. Over the night markets of pleasure.

It is all ornate and dilapidated, and that’s what I find so sincere about it. The first time I traveled to Palermo, my friend remarked lovingly on its grandiose decrepitude.

Everyone will be drinking wine and dancing and swaying by night, right beneath my balcony. Midnight will feel early, like a doorway to somewhere else. Somewhen.

And there will be that familiar cthonic swoon—recognized within the palace of my own body; I was born with it—and I will greet it, and it will greet me in return.

Hello, shadow. Hello, life. Hello, great dark ecstacy.

Everything here appears to be adorned with, of, and by the cycle. The city is a reminder of time’s claws. It is a testimony of the resilience and survival of a people and a place and an ecosystem that emerges from the layers—yet is distinctly of itself, bursting through the relentless pentimento of conquerers and cultures.

My grandmother Concetta Maria Lipari was born in Palermo. She was a child in the streets of La Kalsa—or, al Khalesa, Palermo’s Arabic district—which is said to have once been entirely underwater.

I feel that watery history in my bones. The feeling of being comfortable with(in) the depths—the desire to go underneath the underneath. And then underneath even that. I suppose a poet is always pushing past where the light ends.

I felt this numinousness when I stood at the water’s edge at the Palermo Port, looking at all the little swaying boats framed by the island’s mountains in the background, like a maternal eye watching.

I feel it at the street shrines. I feel it in the gritty dark back streets winding behind cathedrals or the backs of restaurants or where people live and hang their laundry and tend to plants. I feel it when I drunkenly climb the interior courtyard stairwells to my apartment, under the sharp-eyed glare of the Madonna hanging on a cracked hallway wall. I feel it when I eat cannoli at a former convent, adorned in crucifix and memento.

From the family stories told of my “crazy” grandmother, I think she felt it all, too, even if she couldn’t articulate it within the context of her life. I think she carried the island’s story with her as she crossed the Atlantic ocean to emigrate.

I think there was always a heaviness in her—a place-grief, the weight of huge cultural shift, the stamp of poverty, and the relics of war. And then there were mental health issues—many innate, and some that came with the era, her intense devotion to God, and the expectations of the domestic. Seven children.

I was told by a family member that she yearned for things, that she even contained a deep envy—that she had given herself to a life that didn’t bear the fruits of her own desires.

I am not here to answer those questions nor to mythologize and romanticize it all, as I used to do when I was younger.

I am only here to ask and to listen. I am in acknowledgment of my privileges. I am embodied of a curiosity, hunger, indulgence, and devotion that was never available to the women before me. To her.

Even in my lack and limitations, I am a Life that my ancestors could never be permitted to daydream. I return to the places they left. Why? To excavate what? Them? Myself? Something even bigger? To heal? Sometimes I don’t know what I am looking for. But I know that I have only just arrived at the doorway. And I have walked through it.

I feel the salty, sticky hands of its lure on me. I have written about this pull in my book SAINT OF—this reckoning with inarticulable hunger, the need to let the fruits of this wild life drip from my lips.

***

Now I am in Palermo for the second time, and it’s over 100 degrees and I am sweating through my white dress. I am drinking an espresso in a port-side cafe. And then I am pinning up my hair and covering my shoulders and walking alone through the baroque Chiesa del Gesu to visit an idea of god and find respite from the sun. I pray for illumination, even in my chaotic, messy, half-belief.

In 1943, during the war, a bomb destroyed the church's dome—and all of its art and walls and bones—leading to replacement and restoration work in 2009. I feel that I am standing in the palm of time—rewritten or salvaged or reclaimed.

Then a summer later, I’m again in Palermo. I am staying at the childhood home of famous writer Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa (the author of The Leopard—a must-must read about Sicily and Palermo during the Risorgimento).

The home was also destroyed in the war and then rebuilt into the small for-rent apartment it is today, with its bee-buzzy back garden. I think of the poets and writers before me. And the poets, writers, and artists here today. How so much of this city serves as a muse.

I sit in the stillness of its little sundrenched patio and I write poems and let the sun fuck me up until it goes down and the insects change all their songs. I feel completely at home. I run through Italian verbs in the shower as the cool water falls over my golden shoulders. And then I clam up in restaurants even though I know what to say.

I wonder if I am a bad representation of my bloodline. I then wonder if I’m just trying to honor it. I see Sicily in my face.

I find my name etched into the groundwork, & etched into street names.

I am always here for the dark underneath, for the messages, for the shadow.

At the Chiesa San Giovanni Degli Eremiti, the echoes of time persist; it was once a Byzantine chapel and later a mosque. I lay my hands upon the walls and let myself be pulled down and in and under everything. I think of the many cultures who left their imprint here: The Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, Arabs, Normans, the Spanish. And many others.

At the Vucciria market, I visit Saint Michael in a square, standing at the statue’s base, gazing up at him, asking for him to wrap his wings around my whole life. To help relieve my dark desires and prevent me from the delectable temptations of ruinousness.

There’s the 150-year-old ficus tree at Giardino Garibaldi, with its enormous underground roots clinging to the earth. He looks solemn; he has seen so much; he has seen bloodshed. I trust his resolve; I ask for a message.

***

I am married in Palermo at Palazzo Pantelleria in a heady June wedding. On my wedding trip, there is another great ficus tree right at my bedroom window. I would turn to the tree—jutt before my wedding and again afterward—as an anchor and as a friend, its great depth a soft hand. In its presence, I felt its quiet blessing—that I am fortunate to be a blip in this heavy dirge of time.

During our ceremony, everyone was crammed into a great blue room sitting on white wooden chairs. The balcony doors are swung open for an ungenerous breeze and everyone is sweating through linen suits and waving tiny white paper fans. I peered through a keyhole in a door and watched them all. Not once did I feel surreal or out of place. The room felt like I’d been there a thousand years ago.

The summer before then, Ben and I met Francesco, the wonderful, kind gentleman who hosted our wedding in his family home (which is not a wedding venue). We asked if he’d allow us to marry there, and if he could also be present for the ceremony. Si. The building felt like an old friend. So did he. Something in me knew the way, even without ever stepping foot into its rooms. Ah yes, I thought, the yellow parlor. And the terrace. And the way the light falls. I know you.

During our ceremony, I could feel the generations watching me through the windows in my white dress. I could feel them alongside me in the streets as we processed. I could feel my body at the cellular level be returned to some essence of my blood-home, even if Palermo truly could never be home. Even if I will always be foreign, always be a body to-be-returned-to the island but never of it.

Which is enough for me.

I found that my poetry written in Palermo encountered this strange borderland of unbelonging. And I found that it was an honor to love this city, to ask for it to welcome me. To tend to this city of blood and ghosts by learning about it, by returning to it, by creating within it, by buying from its people, by understanding its limitations, its sorrows, its multitudes, by asking questions.

Palermo wasn’t Paris or Prague or Amsterdam or Mexico City or Rio. I have been to those cities, and they are beautiful and full of everything, but I don’t come from them. In Palermo, I feel the tether. I feel its teeth. I feel its hands on me.

***

It’s easy to wander through churches and look for the old gods and talk to my dead in Palermo. I think, even for those who aren’t Sicilian, that this would feel easy. The city bends itself to introspection; it welcomes the dizzying devotion to darkness. It is normal to put your feet on the dark underground, to venture into tombs and visit the saints.

I think this tuning-into the darkness is a wound and a gift. The inherited longing. The grief. The knowledge that this life is short and painful. The want for answers and reconciliation and resolution. The perpetual desire to get into collaboration with God and the creative force and ancestral knowledge.

But Palermo also wants you to indulge. To celebrate. To live.

In this city, I am reminded of this great gift of life—of enjoying the nectars, of family and friends and this ticking body. I drink the volcanic Etna rosso in the streets and I wear little cotton dresses with nothing underneath. I eat arancine, and I eat pasta even in the heat, and I cover everything in pistachio. I talk for hours, I ask people about their lives, I laugh when I fuck up the language, I flirt, I make a romance of everything. I indulge in the aliveness. In the levity. I let myself glitter on the surface of it all. I loom myself into the bacchanalia. I put myself into the beauty and I watch and I breath and I adorn and I laugh. I watch the beautiful men. I watch the beautiful women. I long and I speak Italian and I kiss and I touch.

Palermo holds us in this bottomless, glorious place of asking, of longing, of returning-to, of exploration, of reconciliation, of death and life and celebration.

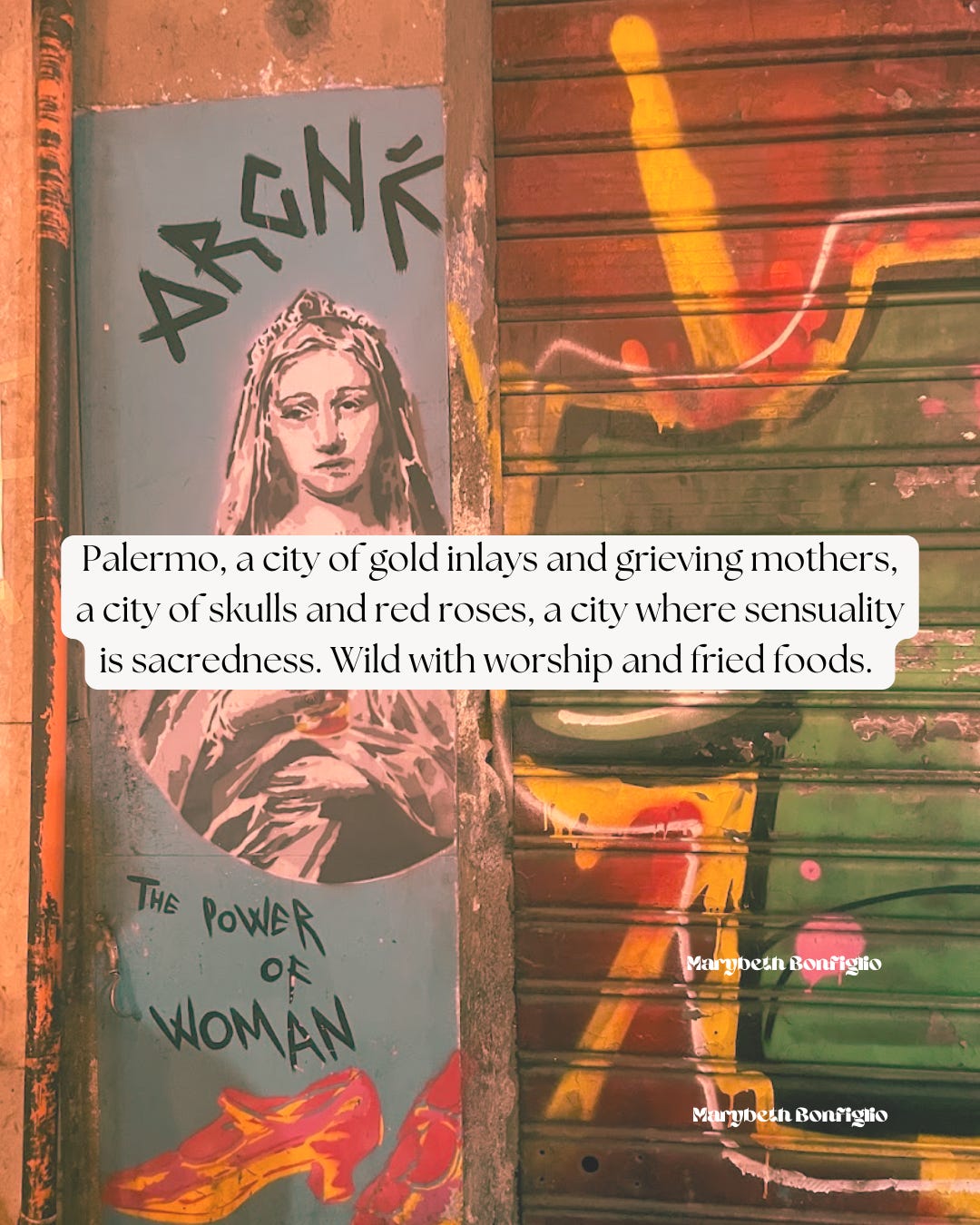

This summer I’ll be returning to Palermo with the immensely talented and deeply devoted MaryBeth Bonfiglio, whose many Radici Siciliane immersions embrace the magic, history, and culture of Sicily.

I’ve been to Sicily with her for an Ancestral Arts immersion, deep in the Madonie region, surrounded by hills and valleys. I’ve witnessed the beauty of seeing Sicily through respectful, enchanted, immersed eyes—not through the sometimes-aggressive and disconnected tourism tactics we often see when away from home.

I am honored to co-guide SOTTERRANEA, a writing immersion, with her in Palermo—our beloved city of cities. Together, we will weave a unique experiential journey that allows us time to reflect on the spectrum: darkness, death, decay, life, and indulgence.

From June 5—June 11 we will gather as an intimate group in the subterranean & poetic city of Palermo, Sicily to explore, experience, and write the sensuality of life and death. If you want to be in this magical space with us, you can find out more here.

Maybe you will find yourself adoring Palermo as I do. And taking its lessons to heart as a writer: Explore every layer.

This was so magical and hit while I’m writing something (fiction) with a similar mood and theme so thank you universe. You have a wonderful ability to conjure the spirit of place, and you’re so very in touch with the muse/eternity/whichever moniker you wish to use for it. I am going to buy Saint Of when we’re next in the US. I wish I could join for the writing workshop. X

I loved this, I adore when people write on their ancestors. You may enjoy the work of Sylvia linsteadt on reclaiming our motherlines.